We'll see what changes occur after the deadline or "disputes" are settled?

"Never let the facts get in the way of a good story." - Mark Twain

Margaret Sanger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This page is currently protected from editing until December 2, 2012 or until disputes have been resolved. This protection is not an endorsement of the current version. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. Please discuss any changes on the talk page; you may use the {{editprotected}} template to ask an administrator to make an edit if it is supported by consensus. You may also request that this page be unprotected. |

| Margaret Sanger | |

|---|---|

Sanger in 1922 | |

| Born | Margaret Higgins September 14, 1879 Corning, New York, United States |

| Died | September 6, 1966 (aged 86) Tucson, Arizona, United States |

| Occupation | Social reformer, sex educator, nurse |

| Spouse(s) | William Sanger (1902–1921)[note 1] James Noah H. Slee (1922–1943) |

Sanger's early years were spent in New York City. In 1914, prompted by suffering she witnessed due to frequent pregnancies and self-induced abortions, she started a monthly newsletter, The Woman Rebel. Sanger's activism was influenced by the conditions of her youth—her mother had 18 pregnancies in 22 years, and died at age 50 of tuberculosis and cervical cancer.

In 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, which led to her arrest for distributing information on contraception. Her subsequent trial and appeal generated enormous support for her cause. Sanger felt that in order for women to have a more equal footing in society and to lead healthier lives, they needed to be able to determine when to bear children. She also wanted to prevent back-alley abortions, which were dangerous and usually illegal at that time.

In 1921, Sanger founded the American Birth Control League, which later became the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. In New York, Sanger organized the first birth control clinic staffed by all-female doctors, as well as a clinic in Harlem with an entirely African-American staff. In 1929, she formed the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control, which served as the focal point of her lobbying efforts to legalize contraception in the United States. From 1952 to 1959, Sanger served as president of the International Planned Parenthood Federation. She died in 1966, and is widely regarded as a founder of the modern birth control movement.

Contents[hide] |

Life

Early life

Margaret Sanger was born as Margaret Higgins in Corning, New York. Her mother, Anne (Purcell) Higgins, was a devout Catholic who went through 18 pregnancies (with 11 live births) in 22 years before dying at age 50 of tuberculosis and cervical cancer.[2][3] Margaret's father, Michael Hennessy Higgins, was a Catholic who became an atheist and an activist for women's suffrage and free public education.[4][5]Sanger's father was born in Ireland and his parents and he emigrated to Canada when he was a child due to the Potato Famine. At fourteen he emigrated to the USA to serve in the U.S. Army during the Civil War, although he had to wait until he was fifteen to serve in the Twelfth New York Volunteer Cavalry, where he was a drummer. After leaving the army he studied medicine and phrenology, but ultimately chose to become a stonecutter, making stone angels, saints, and tombstones.[6] Sanger was the sixth of eleven children,[7] and spent much of her youth assisting with household chores and caring for her younger siblings.

Sanger's sisters paid the tuition for her to attend Claverack College, a boarding school in Claverack, New York, for two years.[8] She returned home in 1896 following her father's request that she come home to nurse her mother, who died three years later in 1899.[9] Toward the end of the century, the mother of one of her Claverack friends arranged for Sanger to enroll in a nursing program at a hospital in White Plains, an affluent New York City suburb.[10]

Social activism

In 1912, after a fire destroyed their home in Hastings-on-Hudson, the Sanger family moved back to New York City, where Margaret began working as a nurse in the East Side slums of Manhattan. Margaret and William became immersed in the radical bohemian culture that was then flourishing in Greenwich Village.[11] They became involved with local intellectuals, artists, socialists, and activists for political reform, including John Reed, Upton Sinclair, Mabel Dodge, and Emma Goldman.[11] Starting in 1911, Sanger wrote a series of articles about sexual education entitled "What Every Mother Should Know" and "What Every Girl Should Know" for the socialist magazine New York Call.[note 2][14] By her days' standards, the articles were extremely frank in their discussion of sexuality, and many New York Call readers were outraged by them, at least one of them wrote a letter in response canceling her subscription. Other readers, however, praised the series for its candor, one stated that the series contained "a purer morality than whole libraries full of hypocritical cant about modesty.[15]In 1913, Sanger worked as a nurse at Henry Street Settlement in New York's Lower East Side, often with poor women who were suffering due to frequent childbirth and self-induced abortions. Searching for something that would help these women, Sanger visited public libraries, but was unable to find information on contraception.[16] These problems were epitomized in a story that Sanger would later recount in her speeches: while Sanger was working as a nurse, she was called to Sadie Sachs' apartment after Sachs had become extremely ill due to a self-induced abortion. Afterward, Sadie begged the attending doctor to tell her how she could prevent this from happening again, to which the doctor simply gave the advice to remain abstinent. A few months later, Sanger was once again called back to the Sachs' apartment — only this time, Sadie was found dead after yet another self-induced abortion.[17][18] Sanger would sometimes end the story by saying, "I threw my nursing bag in the corner and announced ... that I would never take another case until I had made it possible for working women in America to have the knowledge to control birth." Although Sadie Sachs was possibly a fictional composite of several women Sanger had known, this story marks the time when Sanger began to devote her life to help desperate women before they were driven to pursue dangerous and illegal abortions.[18][19]

In 1914, Sanger launched The Woman Rebel, an eight-page monthly newsletter which promoted contraception using the slogan "No Gods, No Masters".[20][note 3][21] Sanger, collaborating with anarchist friends, coined the term "birth control" as a more candid alternative to euphemisms such as "family limitation"[22] and proclaimed that each woman should be "the absolute mistress of her own body."[23] In these early years of Sanger's activism, she viewed birth control as a free-speech issue, and when she started publishing The Woman Rebel, one of her goals was to provoke a legal challenge to the federal anti-obscenity laws which banned dissemination of information about contraception.[24] Sanger also wanted to publish a book that directly described contraceptive options (in contrast to the articles in The Woman Rebel which only indirectly discussed contraception), so she gathered information, much of it from Europe, and published the pamphlet Family Limitation, in direct violation of the Comstock Law.[25]

Sanger was indicted in August 1914 on three counts of violating obscenity laws and a fourth count of "inciting murder and assassination".[26] The incitement charge was based on an article in The Woman Rebel. Afraid that prosecutors might focus on the incitement charge, and that she might be sent to prison without an opportunity to argue for birth control in court, she fled to England under the alias "Bertha Watson" to avoid arrest.[27] While she was in Europe, Sanger's husband distributed a copy of Family Limitation to an undercover postal worker, resulting in a 30 day jail sentence.[11] Sanger's ally Upton Sinclair wrote an open letter of support for Sanger and her husband in The Masses [28] and during her absence, a groundswell of support grew in the United States, and Margaret returned to the United States in October 1915.[29] Noted attorney Clarence Darrow offered to defend Sanger free of charge, but, bowing to public pressure, the government dropped the charges in early 1916.[30]

Birth control movement

Main article: Birth control movement in the United States

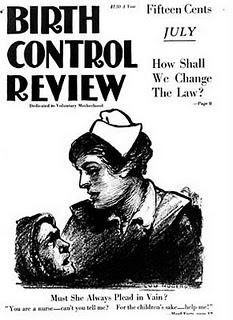

In 1917, she started publishing the monthly periodical The Birth Control Review.[note 4]

On October 16, 1916, Sanger opened a family planning and birth control clinic at 46 Amboy St. in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, the first of its kind in the United States.[31] Nine days after the clinic opened, Sanger was arrested for breaking a New York state law that prohibited distribution of contraceptives, and went to trial in January 1917.[32] Sanger was convicted; the trial judge held that women did not have "the right to copulate with a feeling of security that there will be no resulting conception."[33] Sanger was offered a more lenient sentence if she promised to not break the law again, but she replied: "I cannot respect the law as it exists today."[34] For this, she was sentenced to 30 days in a workhouse.[34] An initial appeal was rejected, but in a subsequent court proceeding in 1918, the birth control movement won a victory when Judge Frederick E. Crane of the New York Court of Appeals issued a ruling which allowed doctors to prescribe contraception.[35] The publicity surrounding Sanger's arrest, trial, and appeal sparked birth control activism across the United States, and earned the support of numerous donors who would provide her with funding and support for future endeavors.[36]

Sanger became estranged from her husband in 1913, and the couple's divorce was finalized in 1921.[37] She had been involved in relationships with Havelock Ellis and H. G. Wells during this period of estrangement.[38]

American Birth Control League

We hold that children should be (1) Conceived in love; (2) Born of the mother's conscious desire; (3) And only begotten under conditions which render possible the heritage of health. Therefore we hold that every woman must possess the power and freedom to prevent conception except when these conditions can be satisfied.After Sanger discovered that physicians were exempt from the law that prohibited the distribution of contraceptive information to women—provided it was prescribed for medical reasons—she established the Clinical Research Bureau (CRB) in 1923 to exploit this loophole.[11][41] The CRB was the first legal birth control clinic in the United States, and it was staffed entirely by female doctors and social workers.[42] The clinic received a large amount funding from John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his family, which continued to make donations to Sanger's causes in future decades, but generally made them anonymously to avoid public exposure of the family name,[43] and to protect family member Nelson Rockefeller's political career since openly advocating birth control could have led to the Catholic Church opposing him politically.[44] John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated five thousand dollars to her American Birth Control League in 1924 and a second time in 1925.[45] In 1922, she traveled to China, Korea, and Japan. In China she observed that the primary method of family planning was female infanticide, and she later worked with Pearl Buck to establish a family planning clinic in Shanghai.[46] Sanger visited Japan six times, working with Japanese feminist Kato Shidzue to promote birth control.[47] This was ironic since ten years earlier Sanger had accused him of murder and praised an attempt to kill him.[48]

In 1926, Sanger gave a lecture on birth control to the women's auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan in Silver Lake, New Jersey.[49] She described it as "one of the weirdest experiences I had in lecturing," and added that she had to use only "the most elementary terms, as though I were trying to make children understand."[49] Sanger's talk was well received by the group, and as a result, "a dozen invitations to similar groups were proffered."[49]

In 1928, conflict within the birth control movement leadership led Sanger to resign as the president of the ABCL and take full control of the CRB, renaming it the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau (BCCRB), marking the beginning of a schism in the movement that would last until 1938.[50]

Sanger invested a great deal of effort communicating with the general public. From 1916 onward, she frequently lectured—in churches, women's clubs, homes, and theaters—to workers, churchmen, liberals, socialists, scientists, and upper-class women.[51] She wrote several books in the 1920s which had a nationwide impact in promoting the cause of birth control. Between 1920 and 1926, 567,000 copies of Woman and the New Race and The Pivot of Civilization were sold.[52] During the 1920s, Sanger received hundreds of thousands of letters, many of them written in desperation by women begging for information on how to prevent unwanted pregnancies.[53] Five hundred of these letters were compiled into the 1928 book, Motherhood in Bondage.[54]

Planned Parenthood era

Main article: Planned Parenthood

Sanger's Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau operated from this New York building from 1930 to 1973.

This 1936 contraception court victory was the culmination of Sanger's birth control efforts, and she took the opportunity, now in her late 50s, to move to Tucson, Arizona, intending to play a less critical role in the birth control movement. In spite of her original intentions, she remained active in the movement through the 1950s.[57]

In 1937, Sanger became chairman of the newly formed Birth Control Council of America, and attempted to resolve the schism between the ABCL and the BCCRB.[58] Her efforts were successful, and the two organizations merged in 1939 as the Birth Control Federation of America.[59][note 6] Although Sanger continued in the role of president, she no longer wielded the same power as she had in the early years of the movement, and in 1942, more conservative forces within the organization changed the name to Planned Parenthood Federation of America, a name Sanger objected to because she considered it too euphemistic.[60]

In 1946, Sanger helped found the International Committee on Planned Parenthood, which evolved into the International Planned Parenthood Federation in 1952, and soon became the world's largest non-governmental international family planning organization. Sanger was the organization's first president and served in that role until she was 80 years old.[61] In the early 1950s, Sanger encouraged philanthropist Katharine McCormick to provide funding for biologist Gregory Pincus to develop the birth control pill.[62]

Death

Legacy

Long after her death, Sanger has continued to be regarded as a leading figure in the battle for American women's rights. Sanger's story has been the subject of several biographies, including an award-winning biography published in 1970 by David Kennedy, and is also the subject of several films, including Choices of the Heart: The Margaret Sanger Story.[64] Sanger's writings are curated by two universities: New York University's history department maintains the Margaret Sanger Papers Project,[65] and Smith College's Sophia Smith Collection maintains the Margaret Sanger Papers collection.[66]Sanger has been recognized with many important honors. In 1957, the American Humanist Association named her Humanist of the Year. Government authorities and other institutions have memorialized Sanger by dedicating several landmarks in her name, including a residential building on the Stony Brook University campus, a room in Wellesley College's library,[67] and Margaret Sanger Square in New York City's Greenwich Village.[68] In 1993, the Margaret Sanger Clinic — where she provided birth control services in New York in the mid twentieth century — was designated as a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service.[69] In 1966, Planned Parenthood began issuing its Margaret Sanger Awards annually to honor "individuals of distinction in recognition of excellence and leadership in furthering reproductive health and reproductive rights."[70]

Many who are opposed to the legalization of abortion frequently condemn Sanger by questioning her fitness as a mother and criticizing her views on race, abortion, and eugenics.[71][72][note 8] In spite of such attacks, Sanger continues to be regarded as an icon for the American reproductive rights movement and woman's rights movement.

Views and opinions

Sexuality

While researching information on contraception Sanger read various treatises on sexuality in order to find information about birth control. She read The Psychology of Sex by the English psychologist Havelock Ellis and was heavily influenced by it.[73] While traveling in Europe in 1914, Sanger met Ellis.[74] Influenced by Ellis, Sanger adopted his view of sexuality as a powerful, liberating force.[75] This view provided another argument in favor of birth control, as it would enable women to fully enjoy sexual relations without the fear of an unwanted pregnancy.[76] Sanger also believed that sexuality, along with birth control, should be discussed with more candor.[75]However, Sanger was opposed to excessive sexual indulgence. She stated "every normal man and woman has the power to control and direct his sexual impulse. Men and women who have it in control and constantly use their brain cells thinking deeply, are never sensual." [77][78] Sanger said that birth control would elevate women away from a position of being an object of lust and elevate sex away from purely being for satisfying lust, saying that birth control "denies that sex should be reduced to the position of sensual lust, or that woman should permit herself to be the instrument of its satisfaction." [79] Sanger wrote that masturbation was dangerous. She stated "In my personal experience as a trained nurse while attending persons afflicted with various and often revolting diseases, no matter what their ailments, I never found any one so repulsive as the chronic masturbator.It would not be difficult to fill page upon page of heart-rending confessions made by young girls, whose lives were blighted by this pernicious habit, always begun so innocently." [80] She believed that women had the ability to control their sexual impulses, and should utilize that control to avoid sex outside of relationships marked by "confidence and respect." She believed that exercising such control would lead to the "strongest and most sacred passion."[81] However, Sanger was not opposed to homosexuality and praised Ellis for clarifying "the question of homosexuals... making the thing a—not exactly a perverted thing, but a thing that a person is born with different kinds of eyes, different kinds of structures and so forth... that he didn't make all homosexuals perverts—and I thought he helped clarify that to the medical profession and to the scientists of the world as perhaps one of the first ones to do that."[82] Sanger believed sex should be discussed with more candor, and praised Ellis for his efforts in this direction. She also blamed the suppression of discussion about it on Christianity.[82]

Eugenics

As part of her efforts to promote birth control, Sanger found common cause with proponents of eugenics, believing that they both sought to "assist the race toward the elimination of the unfit."[83] Sanger was a proponent of negative eugenics, which aims to improve human hereditary traits through social intervention by reducing reproduction by those considered unfit. Sanger's eugenic policies included an exclusionary immigration policy, free access to birth control methods and full family planning autonomy for the able-minded, and compulsory segregation or sterilization for the profoundly retarded.[84][85] In her book The Pivot of Civilization, she advocated coercion to prevent the "undeniably feeble-minded" from procreating.[86] Although Sanger supported negative eugenics, she asserted that eugenics alone was not sufficient, and that birth control was essential to achieve her goals.[87][88][89]In contrast with eugenicists who advocated euthanasia for the unfit,[note 9] Sanger wrote, "we [do not] believe that the community could or should send to the lethal chamber the defective progeny resulting from irresponsible and unintelligent breeding."[90] Similarly, Sanger denounced the aggressive and lethal Nazi eugenics program.[85] In addition, Sanger believed the responsibility for birth control should remain in the hands of able-minded individual parents rather than the state, and that self-determining motherhood was the only unshakable foundation for racial betterment.[87][91]

Sanger also supported restrictive immigration policies. In "A Plan for Peace", a 1932 essay, she proposed a congressional department to address population problems. She also recommended that immigration exclude those "whose condition is known to be detrimental to the stamina of the race," and that sterilization and segregation be applied to those with incurable, hereditary disabilities.[84][85][92]

Race

From 1939 to 1942 Sanger was an honorary delegate of the Birth Control Federation of America, which included a supervisory role — alongside Mary Lasker and Clarence Gamble — in the Negro Project, an effort to deliver birth control to poor African Americans.[98] Sanger wanted the Negro Project to include black ministers in leadership roles, but other supervisors did not. To emphasize the benefits of involving black community leaders, she wrote to Gamble "we do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members." This quote has been mistakenly used by Angela Davis, to support her claims that Sanger wanted to exterminate black people.[99] However, New York University's Margaret Sanger Papers Project, clarifies that Sanger, in writing that letter, "recognized that elements within the black community might mistakenly associate the Negro Project with racist sterilization campaigns in the Jim Crow South, unless clergy and other community leaders spread the word that the Project had a humanitarian aim."[100]

Freedom of speech

Sanger opposed censorship throughout her career, with a zeal comparable to her support for birth control. Sanger grew up in a home where iconoclastic orator Robert Ingersoll was admired.[101] During the early years of her activism, Sanger viewed birth control primarily as a free-speech issue, rather than a feminist issue, and when she started publishing The Woman Rebel in 1914, she did so with the express goal of provoking a legal challenge to the Comstock laws banning dissemination of information about contraception.[24] In New York, Emma Goldman introduced Sanger to members of the Free Speech League, such as Edward Bliss Foote and Theodore Schroeder, and subsequently the League provided funding and advice to help Sanger with legal battles.[102]Over the course of her career, Sanger was arrested at least eight times for expressing her views during an era in which speaking publicly about contraception was illegal.[103] Numerous times in her career, local government officials prevented Sanger from speaking by shuttering a facility or threatening her hosts.[104] In Boston in 1929, city officials under the leadership of James Curley threatened to arrest her if she spoke — so she turned the threat to her advantage and stood on stage, silent, with a gag over her mouth, while her speech was read by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.[105]

Abortion

Sanger's family planning advocacy always focused on contraception, rather than abortion.[106][note 10] It was not until the mid-1960s, after Sanger's death, that the reproductive rights movement expanded its scope to include abortion rights as well as contraception.[note 11] Sanger was opposed to abortions, both because they were dangerous for the mother in the early 20th century and because she believed that life should not be terminated after conception. In her book Woman and the New Race, she wrote, "while there are cases where even the law recognizes an abortion as justifiable if recommended by a physician, I assert that the hundreds of thousands of abortions performed in America each year are a disgrace to civilization."[109]Historian Rodger Streitmatter concluded that Sanger's opposition to abortion stemmed from concerns for the dangers to the mother, rather than moral concerns.[110] However, in her 1938 autobiography, Sanger noted that her opposition to abortion was based on the taking of life: "[In 1916] we explained what contraception was; that abortion was the wrong way no matter how early it was performed it was taking life; that contraception was the better way, the safer way—it took a little time, a little trouble, but was well worth while in the long run, because life had not yet begun."[111] And in her book Family Limitation, Sanger wrote that "no one can doubt that there are times when an abortion is justifiable but they will become unnecessary when care is taken to prevent conception. This is the only cure for abortions."[112]

Works

- Books and pamphlets

- What Every Mother Should Know — Originally published in 1911 or 1912, based on a series of articles Sanger published in 1911 in the New York Call, which were, in turn, based on a set of lectures Sanger gave to groups of Socialist party women in 1910–1911.[113] Multiple editions published through the 1920s, by Max N. Maisel and Sincere Publishing, with the title What Every Mother Should Know, or how six little children were taught the truth ... Online (1921 edition, Michigan State University)

- Family Limitation — Originally published 1914 as a 16 page pamphlet; also published in several later editions. Online (1917, 6th edition, Michigan State University)

- What Every Girl Should Know — Originally published 1916 by Max N. Maisel; 91 pages; also published in several later editions. Online (1920 edition); Online (1922 ed., Michigan State University)

- The Case for Birth Control: A Supplementary Brief and Statement of Facts — May 1917, published to provide information to the court in a legal proceeding. Online (Google Books)

- Woman and the New Race, 1920, Truth Publishing, forward by Havelock Ellis. Online (Harvard University); Online (Project Gutenberg); Online (Google Books)

- Debate on Birth Control — 1921, text of a debate between Sanger, Theodore Roosevelt, Winter Russell, George Bernard Shaw, Robert L. Wolf, and Emma Sargent Russell. Published as issue 208 of Little Blue Book series by Haldeman-Julius Co. Online (1921, Michigan State University)

- The Pivot of Civilization, 1922, Brentanos. Online (1922, Project Gutenberg); Online (1922, Google Books)

- Motherhood in Bondage, 1928, Brentanos. Online (Google books).

- My Fight for Birth Control, 1931, New York: Farrar & Rinehart

- An Autobiography. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press. 1938. ISBN 0-8154-1015-8.

- Periodicals

- The Woman Rebel — Seven issues published monthly from March 1914 to August 1914. Sanger was publisher and editor.

- Birth Control Review — Published monthly from February 1917 to 1940. Sanger was Editor until 1929, when she resigned from the ABCL.[114] Not to be confused with Birth Control News, published by the London-based Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress.

- Collections and anthologies

- Sanger, Margaret, The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1: The Woman Rebel, 1900–1928, Esther Katz, Cathy Moran Hajo, Peter Engelman (Eds.), University of Illinois Press, 2003

- Sanger, Margaret, The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 2: Birth Control Comes of Age, 1928–1939, Esther Katz, Cathy Moran Hajo, Peter Engelman (Eds.), University of Illinois Press, 2007

- Sanger, Margaret, The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 3: The Politics of Planned Parenthood, 1939–1966, Esther Katz, Cathy Moran Hajo, Peter Engelman (Eds.), University of Illinois Press, 2010

- Works by Margaret Sanger at Project Gutenberg

- The Margaret Sanger Papers at Smith College

- The Margaret Sanger Papers Project at New York University

- McElderry, Michael J. (1976). "Margaret Sanger: A Register of Her Papers in the Library of Congress". Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2009-03-29. http://web.archive.org/web/20090329075207/http://www.loc.gov/rr/mss/text/sanger.html. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- Correspondence between Sanger and McCormick, from The Pill documentary movie; supplementary material, PBS, American Experience (producers). online.

See also

Notes

- ^ They became estranged in 1913, but the divorce was not finalized until 1921.[1]

- ^ Sanger wrote two series of articles for the New York Call: "What Every Mother Should Know" (1911–1912) and "What Every Girl Should Know'" (1912–1913). Both were later published in book form in 1916.[12][13]

- ^ The slogan "No Gods, No Masters" originated in a flyer distributed by the IWW in the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike.

- ^ The first issue of Birth Control Review was published Feb 1917

- ^ Caption at the bottom of this 1919 issue reads: "Must She Always Plead in Vain? 'You are a nurse — can you tell me? For the children's sake — help me!'"

- ^ Date of merger recorded as 1938 (not 1939) in: O'Conner, Karen, Gender and Women's Leadership: A Reference Handbook, p 743. O'Conner cites Gordon (1976)

- ^ In 1965, the case had struck down one of the remaining contraception-related Comstock laws in Connecticut and Massachusetts. However, Griswold only applied to marital relationships. A later case, Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), extended the Griswold holding to unmarried persons as well.

- ^ A typical pro-life publication critical of Sanger is: Franks, Angela, Margaret Sanger's eugenic legacy: the control of female fertility, McFarland, 2005

- ^ For example, in William Robinson's book, Eugenics, Marriage and Birth Control (Practical Eugenics), Robinson wrote, 'The best thing would be to gently chloroform these [unfit] children or give them a dose of potassium cyanide.'"

- ^ For a discussion of Sanger in relation to abortion see: Hitchcock, Susan Tyler, Roe v. Wade: protecting a woman's right to choose[107]

- ^ Sanger died in 1966, the same year the National Organization for Women was founded and reproductive rights advocates started to strongly campaign for legalized abortion rights, which culminated in the 1973 Roe v Wade Supreme Court decision.[108]

References

- ^ Baker, p 126

- ^ Cox, p 4; Steinem, Gloria (1998-04-13). "Time's 100 Most Important People of the Century: Margaret Sanger". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,988152,00.html.

- ^ Chesler, p 41 (age 50; age 49 in other sources).

Buchanan, p 121 (diseases) - ^ "Margaret Sanger". Infidels.org. http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/john_murphy/margaretsanger.html. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ Rosalind Rosenberg, Divided lives: American women in the twentieth century, p 82; Sanger, Autobiography, p 13.

- ^ Sanger, Margaret The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger Dover Publications Mineola, New York pages 1-3

- ^ Cooper, James L.; Cooper, Sheila M. (1973). The Roots of American Feminist Thought. Alvin and Bacon. p. 219. ASIN B002VY8L0O.

- ^ Baker, p 23

- ^ The selected papers, Vol 1, p 4

- ^ The selected papers, Vol 1, pp 4–5

- ^ a b c d e Chesler, Ellen (1992). Woman of valor: Margaret Sanger and the birth control movement in America. New York: Simon Schuster. ISBN 0-671-60088-5.

- ^ http://www.utexas.edu/opa/blogs/culturalcompass/2010/11/04/what-every-girl-should-know-the-birth-control-movement-in-the-1910s/

- ^ Engelman, p 32:

- ^ Blanchard, Revolutionary sparks: freedom of expression in modern America , p 50. Baker, p 69. Coates p 49

- ^ Chesler, Ellen Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America Simon and Schuster New York pages 65-66

- ^ Endres, Kathleen L., Women's periodicals in the United States: social and political issues, p 448; Endres cites Sanger, An Autobiography, pp 95–96. Endres cites Kennedy, p 19, as pointing out that some materials on birth control were available in 1913.

- ^ Lader (1955), pp 44–50

Baker, pp 49–51

Kennedy, pp 16–18 - ^ a b Viney, Wayne; King, D. A. (2003). A history of psychology: ideas and context. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-33582-9.

- ^ Composite story: The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1, p 185. This source identifies the source of Sanger's quote as: "Birth Control", Library of Congress collection of Sanger's papers: microfilm: reel 129: frame 12, April 1916

- ^ Kennedy, pp 1,22.

- ^ Sanger, Margaret The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger Dover Printing Publications Inc. Mineola New York 2004 pages 111-112

- ^ Sanger, The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1, p 70

Galvin, Rachel. Margaret Sanger's "Deeds of Terrible Virtue" Humanities, National Endowment for the Humanities, September/October 1998, Volume 19/Number 5 - ^ Engelman, Peter C, "Margaret Sanger", article in Encyclopedia of leadership, Volume 4, George R. Goethals, et al (Eds), SAGE, 2004, p 1382

Engelman cites facsimile edited by Alex Baskin, Woman Rebel, New York: Archives of Social History, 1976. Facsimile of original. - ^ a b McCann 2010 pp 750–1

- ^ Engelman p 34; Rosenbaum, p 252

- ^ Chesler, p 102.

- ^ Baker, p 89

- ^ http://wyatt.elasticbeanstalk.com/mep/MS/xml/bsinclau.html

- ^ Kennedy, David M. (1970). "3". Birth Control in America. Yale University Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-300-01495-3. http://books.google.com/?id=-CojUQpSS6wC.

- ^ Sanger, Autobiography, pp 183–9

- ^ Selected Papers, vol 1, p 199

Baker, p 115 - ^ Engelman, p 101

- ^ Lepore, Jill (November 14, 2011). "Birthright: What's next for Planned Parenthood?". New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/11/14/111114fa_fact_lepore. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Cox, p 65

- ^ Engelman, pp 101–3

- ^ McCann 2010, p 751

- ^ Cox, p 76

- ^ Chesler, pp 182, 186

- ^ Freedman, Estelle B., The essential feminist reader, Random House Digital, Inc., 2007 p 211.

- ^ "Birth control: What it is, How it works, What it will do", The Proceedings of the First American Birth Control Conference, Nov 11,12 1921, pp 207–8

The Birth Control Review, Vol V. Num 12, December 1921, Margaret Sanger (Ed), p 18.

Sanger, Pivot of Civilization, 2001 reprint edited by Michael W. Perry, p 409

These principles were adopted at the first meeting of the ABCL in late 1921 - ^ Baker, p 196

- ^ Baker, pp 196–197

The Selected Papers, Vol 2, p 54 - ^ Chesler, pp 277, 293, 558

Harr, John Ensor; Johnson, Peter J. (1988). The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 191, 461–62. — crucial, anonymous Rockefeller grants to the Clinical Research Bureau and support for population control - ^ Chesler, Ellen Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America Simon and Schuster New York 1992 page 425

- ^ Katz, Esther Sanger, Margaret The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger Volume 1: The Woman Rebel University of Illinois Press 2003 page 430

- ^ Cohen, pp 64–5

- ^ Baker, p 275

Katō, Shidzue, Facing two ways: the story of my life, Stanford University Press, 1984, p xxviii

D'Itri, Patricia Ward, Cross currents in the international women's movement, 1848–1948, Popular Press, 1999pp 163–167 - ^ Katz, Esther edited Sanger, Margaret The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger Volume 1: The Woman Rebel 1900-1928 University of Illinois Press Urbana and Chicago 2003 page 421

- ^ a b c Sanger, Margaret (1938). Margaret Sanger, An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 361, 366–7.

- ^ McCann (1994), pp 177–8

"MSPP > About > Birth Control Organizations > Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau". Nyu.edu. 2005-10-18. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/aboutms/organization_bccrb.html. Retrieved 2009-10-07. - ^ Sanger, Margaret (2004). The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger. Courier Dover Publications. p. 366. ISBN 0-486-43492-3.

- ^ Baker p 161

Cohen, p 63 - ^ ""Motherhood in Bondage," #6, Winter 1993/4". Margaret Sanger Papers Project. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/newsletter/articles/motherhood_in_bondage.html. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

The number of letters is reported as "a quarter million", "over a million", or "hundreds of thousands" in various sources - ^ 500 letters: Cohen, p 65.

Sanger, Margaret (2000). Motherhood in bondage. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0837-1. - ^ NYU Margaret Sanger Papers Project "National Committee on Federal Legislation on Birth Control"

- ^ Rose, Melody, Abortion: a documentary and reference guide, ABC-CLIO, 2008, p 29

- ^ a b ""Biographical Note", Smith College, Margaret Sangers Papers". Asteria.fivecolleges.edu. 1966-09-06. http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss43_bioghist.html. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ NYU Margaret Sanger Papers Project "Birth Control Council of America"

- ^ The Margaret Sanger Papers (2010 [last update]). "MSPP > About > Birth Control Organizations > PPFA". nyu.edu. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/aboutms/organization_ppfa.html. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Chesler, p 393

NYU - ^ Ford, Lynne E., Encyclopedia of women and American politics, p 406

Esser-Stuart, Joan E., "Margaret Higgins Sanger", in Encyclopedia of social welfare history in North America, Herrick, John and Stuart, Paul (Eds), SAGE, 2005 p 323 - ^ Engelman, Peter, "McCormick, Katharine Dexter", in Encyclopedia of Birth Control, Vern L. Bullough (Ed.), ABC-CLIO, 2001, pp 170–1

Marc A. Fritz, Leon Speroff, Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010, pp 959–960 - ^ Baker, p 307

- ^ Choices of the Heart — 1995, starring Dana Delany and Henry Czerny, "'Choices of the Heart: The Margaret Sanger Story (1995)'". IMDb (The Internet Movie Database). 1995-03-08. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0112664/. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

Portrait of a Rebel: The Remarkable Mrs. Sanger , TV movie, 1980, starring Bonnie Franklin as Sanger; IMDB - ^ "NYU Sanger Papers Project web site". Nyu.edu. 2007-02-07. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ "Smith College collection web site". Asteria.fivecolleges.edu. http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss43_main.html. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ "Friends of the Library Newsletter". Wellesley.edu. http://www.wellesley.edu/Library/Fr-news/16Spring2003/friends16.html. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ Kayton, Bruce (2003). Radical Walking Tours of New York City. New York: Seven Stories Press. p. 111. ISBN 1-58322-554-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=dLu6zRsKRTIC&lpg=PA111&dq=%22Margaret%20Sanger%20Square%22&pg=PA111#v=onepage&q=%22Margaret%20Sanger%20Square%22&f=false. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ^ "National Historic Landmark Program". Tps.cr.nps.gov. 1993-09-14. http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceId=2157&ResourceType=Building. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ "Rockefeller 3d Wins Sanger Award". New York Times. 1967-10-09. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0615F93D5B117B93CBA9178BD95F438685F9. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

"Planned Parenthood Salutes Visionary Leaders in the Fight for Reproductive Freedom." Press release in Business Wire 29 Mar. 2003: 5006. General OneFile. Web. 11 Feb. 2011.

Lozano, Juan (March 27, 2009). "Clinton champions women's rights worldwide". Houston Chronicle. http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/metropolitan/6347110.html. Retrieved February 14, 2011.[dead link] - ^ Marshall, Robert G.; Donovan, Chuck (October 1991). Blessed Are the Barren: The Social Policy of Planned Parenthood. Fort Collins, CO: Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-353-0; ISBN 978-0-89870-353-5.

- ^ "Minority Anti-Abortion Movement Gains Steam". NPR. September 24, 2007. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14650805. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ Sanger, Margaret The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger Dover Publications Inc Mineola New York 2004 page 94

- ^ Cox, p 55

- ^ a b Chesler, pp 13–14

- ^ Chesler

Kennedy, p 127 - ^ http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/webedition/app/documents/show.php?sangerDoc=304923.xml

- ^ Bronski, Michael A Queer History of the United States page 100 Beacon Press 2011

- ^ Sanger, Margaret The Pivot of Civilization Humanity Books Amherst New York 2003 page 204

- ^ http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/webedition/app/documents/show.php?sangerDoc=304922.xml

- ^ Bronski, Michael, A Queer History of the United States, Beacon Press, 2011

Quotes from Sanger, "What Every Girl should know: Sexual Impulses Part II", in New York Call, Dec 29, 1912; also in the subsequent book What Every Girl Should Know pp 40–48; reprinted in The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1, pp 41–5 (quotes on p 45) - ^ a b http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/multimedia/video/2008/wallace/sanger_margaret_t.html

- ^ Engelman, p 132

- ^ a b Porter, Nicole S.; Bothne Nancy; Leonard, Jason (2008-02-01). Evans, Sophie J.. ed. Public Policy Issues Research Trends. Nova Science. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-60021-873-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=8FimyKiZOXUC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=Sanger&f=false.

- ^ a b c "The Sanger-Hitler Equation", Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter, #32, Winter 2002/3. New York University Department of History

- ^ Sanger, Pivot, p 181; quoted in Charles Valenza: "Was Margaret Sanger a Racist?" Family Planning Perspectives, January–February 1985, page 44.

- ^ a b Sanger, Margaret, "Birth Control and Racial Betterment", Birth Control Review, Feb. 1919, pp 11–12, Online

- ^ Franks, Angela (2005). Margaret Sanger's eugenic legacy: the control of female fertility. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7864-2011-7.

- ^ Freedman, Estelle B. (2007). The essential feminist reader. Modern Library. p. 211.

- ^ Black, Edwin (September 2003) [2003]. The War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. New York City, NY: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 1-56858-258-7., p 251.

Sanger's quote from The Pivot of Civilization, p 100 - ^ Margaret Sanger. "The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda." Birth Control Review, October 1921, page 5

- ^ Sanger, "A Plan For Peace", Birth Control Review, April 1932, p. 106. Online

- ^ Baker, p 200

- ^ McCann (1994), pp 150–4. Bigotry: p 153.

See also p 45, The selected papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 1 - ^ Hajo, p. 85

- ^ Hajo, p. 85

From Planned Parenthood: "The Truth about Margaret Sanger". Planned Parenthood Federation of America. http://www.plannedparenthoodnj.org/library/topic/contraception/margaret_sanger.:In 1930, Sanger opened a family planning clinic in Harlem that sought to enlist support for contraceptive use and to bring the benefits of family planning to women who were denied access to their city's health and social services. Staffed by a black physician and black social worker, the clinic was endorsed by The Amsterdam News (the powerful local newspaper), the Abyssinian Baptist Church, the Urban League, and the black community's elder statesman, W. E. B. Du Bois.

- ^ Planned Parenthood Federation of America (2004). "The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Upon Accepting the Planned Parenthood Sanger Award". http://www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/who-we-are/reverend-martin-luther-king-jr-4728.htm.

- ^ Engelman, p 175

Birth Control Federation of America, The Margaret Sanger Papers Project

"Birth Control or Race Control? Sanger and the Negro Project". Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter (Margaret Sanger Papers Project) (28). 2002-11-14. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/newsletter/articles/bc_or_race_control.html. Retrieved 2009-01-25. - ^ "Birth Control or Race Control? Sanger and the Negro Project". Margaret Sanger Papers Project Newsletter (Margaret Sanger Papers Project) (28). 2002-11-14. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/newsletter/articles/bc_or_race_control.html. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Smear n Fear", New York University, History Department, Margaret Sanger Papers Project, 2010, [1]

- ^ "The Child Who Was Mother to a Woman" from The New Yorker, April 11, 1925, page 11.

- ^ Wood, Janice Ruth (2008), The struggle for free speech in the United States, 1872–1915: Edward Bliss Foote, Edward Bond Foote, and anti-Comstock operations, Psychology Press, 2008, pp 100–102

- ^ "Every Child a Wanted Child", Time, Sept 16, 1966, p 96.

- ^ Kennedy, p 149

- ^ Melody, Michael Edward (1999), Teaching America about sex: marriage guides and sex manuals from the late Victorians to Dr. Ruth, NYU Press, 1999, p 53 (citing Halberstam, David, The Fifties, Villard. 1993, p 285)

Davis, Tom, Sacred work: Planned Parenthood and its clergy alliances Rutgers University Press, 2005, p 213 (citing A Tradition of Choice, Planned Parenthood, 1991, p 18) - ^ Baker, p 3

- ^ Infobase Publishing, 2006, pp 29–35

- ^ Engelman, pp 181–5

- ^ Margaret Sanger (1920). "Contraceptives or Abortion?". Woman and the New Race. http://www.bartleby.com/1013/10.html.

- ^ Streitmatter, Rodger (2001). Voices of Revolution: The Dissident Press in America. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-231-12249-7.

- ^ Sanger, Margaret (1938). Margaret Sanger, An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 217.

- ^ Gray, p 280, citing 1916 edition: Sanger, Margaret (1917). Family Limitation. p. 5. http://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/AmRad/familylimitations.pdf.

- ^ Coates, p 48

Hoolihan, Christopher (2004), An Annotated Catalogue of the Edward C. Atwater Collection of American Popular Medicine and Health Reform, Vol 2 (M–Z), University Rochester Press, p 299 - ^ ""Birth Control Review", Margaret Sanger Papers Project, NYU". Nyu.edu. http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sanger/secure/aboutms/organization_bcr.html. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

Bibliography

- Baker, Jean H. (2011), Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion, Macmillan

- Buchanan, Paul D. (2009), American Women's Rights Movement: A Chronology of Events and of Opportunities from 1600 to 2008, Branden Books

- Chesler, Ellen (1992). Woman of valor: Margaret Sanger and the birth control movement in America. New York: Simon Schuster. ISBN 0-671-60088-5.

- Coates, Patricia Walsh (2008), Margaret Sanger and the origin of the birth control movement, 1910–1930: the concept of women's sexual autonomy, Edwin Mellen Press, 2008

- Cohen, Warren I. (2009), Profiles in humanity: the battle for peace, freedom, equality, and human rights, Rowman & Littlefield

- Coigney, Virginia (1969), Margaret Sanger: rebel with a cause, Doubleday

- Cox, Vicki (2004). Margaret Sanger: Rebel For Women's Rights. Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 0-7910-8030-7.

- Engelman, Peter C. (2011), A History of the Birth Control Movement in America, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-36509-6

- Franks, Angela (2005), Margaret Sanger's eugenic legacy: the control of female fertility, McFarland

- Gordon, Linda (1976). Woman's Body, Woman's Right:A Social History of Birth Control in America. New York: Grossman Publishers.

- Gray, Madeline (1979). Margaret Sanger: A Biography of the Champion of Birth Control. New York City, NY: Richard Marek Publishers. ISBN 0-399-90019-5.

- Hajo, Cathy Moran (2010), Birth Control on Main Street: Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916–1939, University of Illinois Press ISBN 978-0-252-03536-4

- Kennedy, David (1970). Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger. Yale University Press.

- Lader, Lawrence (1955), The Margaret Sanger Story and the Fight For Birth Control, Doubleday. Reprinted in Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1975 ISBN 978-0-8371-7076-3.

- Lader, Lawrence and Meltzer, Milton (1969), Margaret Sanger: pioneer of birth control, Crowell

- McCann, Carole Ruth (1994), Birth control politics in the United States, 1916–1945 , Cornell University Press

- McCann, Carole Ruth (2010), "Women as Leaders in the Contraceptive Movement", in Gender and Women's Leadership: A Reference Handbook, Karen O'Connor (Ed), SAGE

- Reed, Miriam (2003), Margaret Sanger: Her Life in Her Words, Barricade Books, ISBN 1-56980-246-7.

- Rosenbaum, Judith (2010), "The Call to Action: Margaret Sanger, the Brownsville Jewish Women, and Political Activism", in Gender and Jewish History, Marion A. Kaplan, Deborah Dash Moore (Eds), Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Viney, Wayne; King, D. A. (2003). A history of psychology: ideas and context. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-33582-9.

External links

- Interview conducted by Mike Wallace , Sept. 21, 1957. Hosted at the Harry Ransom Center.

- March for Women's Lives, April 26, 2004; AlexanderSanger.com(Alexander Sanger, grandson of Margaret Sanger)

- Margaret Sanger; findagrave.com

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

- 1879 births

- 1966 deaths

- American atheists

- American birth control activists

- American eugenicists

- American feminists

- American humanists

- American nurses

- American people of Irish descent

- American socialists

- American women's rights activists

- Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery

- Free speech activists

- Members of the Socialist Party of America

- Industrial Workers of the World members

- People from Greenwich Village, New York

- People from Steuben County, New York

- Planned Parenthood

- Sex educators